What if the greatest threat to your health was silently damaging your organs right now, without a single symptom to warn you? How would you feel knowing that a condition affecting nearly half of all adults worldwide is quietly increasing your risk of heart attack, stroke, and kidney failure with each passing day? For millions of people with undiagnosed or poorly controlled high blood pressure, this scenario isn’t hypothetical—it’s reality. While most people understand that hypertension isn’t desirable, few truly grasp the extensive and potentially devastating complications of high blood pressure throughout the body.

High blood pressure—medically known as hypertension—earns its reputation as the “silent killer” because it typically causes no symptoms while progressively damaging blood vessels in vital organs. The consequences only become apparent after years of undetected harm. A blood pressure reading of 130/80 mmHg or higher doesn’t just represent numbers on a medical chart; it signals a significantly increased risk of serious, life-altering complications affecting your heart, brain, kidneys, eyes, and more.

At IFitCenter, we’ve observed countless patients who were unaware of how their elevated blood pressure readings were affecting their bodies until complications began to emerge. This comprehensive guide examines the full spectrum of high blood pressure complications, explaining exactly how hypertension damages different organ systems and why understanding these risks is crucial for anyone concerned about their long-term health.

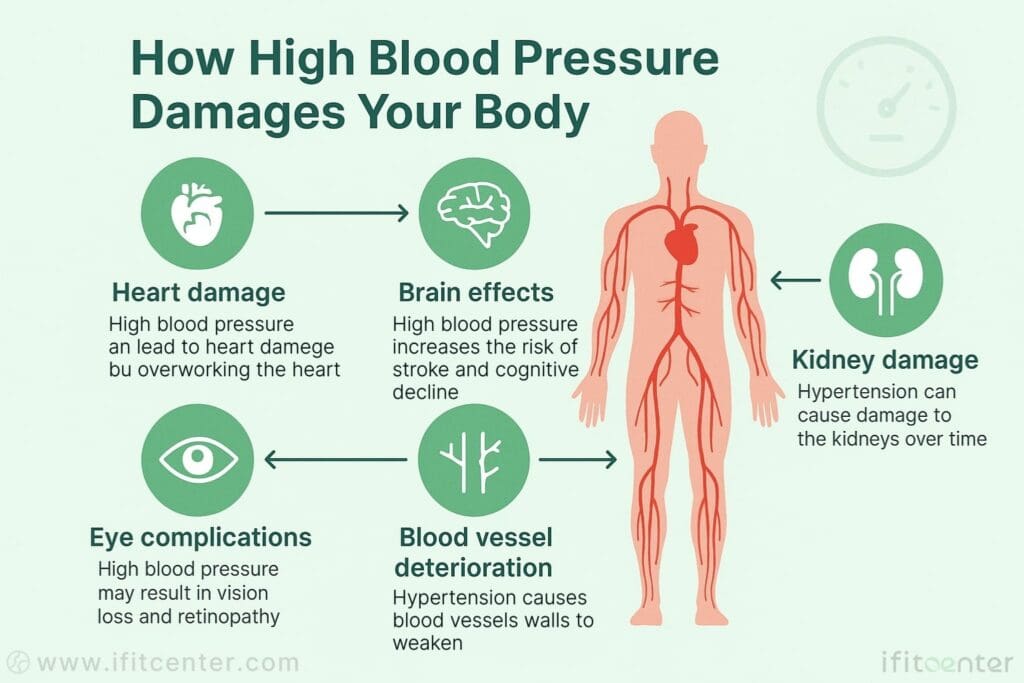

How High Blood Pressure Damages Your Body

Blood pressure is the force that blood exerts against your artery walls as it flows through your body. This pressure is measured using two numbers: systolic and diastolic. The top number (systolic) measures pressure when your heart contracts, while the bottom number (diastolic) measures pressure when your heart relaxes between beats.

Normal blood pressure is below 120/80 mmHg. When readings consistently reach 130/80 mmHg or higher, you have high blood pressure or hypertension. The higher these numbers climb, the more stress is placed on your blood vessels.

The Mechanism of Vascular Damage

Think of your arteries like a garden hose. When water pressure inside the hose is normal, the hose remains flexible and functions properly. But when pressure becomes too high, the hose begins to stiffen, develop tiny cracks, and eventually weaken.

Similarly, when blood pressure remains elevated, it damages the endothelial cells that line your artery walls. These cells act as a protective barrier, but under constant high pressure, they become injured. The body attempts to repair this damage by sending inflammatory cells and substances to the area, which unfortunately can make the situation worse.

On the IFitCenter blog, we have prepared a free information database about various diseases, including high blood pressure, for you, our dear readers. By reviewing these resources, you will gain valuable information for controlling and preventing these conditions. To access the first part of the information, you can use the links below:

- what is a normal blood pressure?

- signs of high blood pressure

- normal blood pressure chart

- secondary cause of hypertension

- measure blood pressure at home

- healthy eating to lower blood pressure

Atherosclerosis Development

As damage continues, cholesterol, fat, calcium, and other substances in your blood begin to collect at these injured sites. Over time, these deposits form plaque that narrows the arteries, making them less flexible and restricting blood flow. This condition is called atherosclerosis.

The narrowed arteries force your heart to work harder to pump blood, creating a dangerous cycle that further raises blood pressure. As atherosclerosis progresses, the risk of blood clots increases, which can block blood flow completely in critical arteries.

The Silent Timeline of Damage

What makes high blood pressure particularly dangerous is that this damage occurs without noticeable symptoms in most people. For years or even decades, elevated blood pressure can silently harm your blood vessels while you feel perfectly fine. By the time symptoms appear, significant damage has often already occurred.

The timeline varies from person to person, but research shows that each increment of blood pressure above normal increases the risk of complications. Even moderately elevated blood pressure can cause substantial damage over time if left untreated.

Long-term Effects Across Body Systems

The vascular damage from high blood pressure affects nearly every major organ in your body because all organs depend on healthy blood vessels for oxygen and nutrients. Over time, this damage can lead to serious complications in multiple body systems:

- In your heart: increased risk of heart attack, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation

- In your brain: higher chance of stroke, vascular dementia, and cognitive decline

- In your kidneys: progressive kidney damage that can lead to kidney failure

- In your eyes: vision problems and potential blindness from damaged blood vessels

- In your limbs: peripheral artery disease that can cause pain and mobility issues

The damage doesn’t occur overnight, but rather accumulates gradually as blood pressure remains elevated. This is why high blood pressure is often called a “silent killer” – it causes serious harm without obvious warning signs until complications develop.

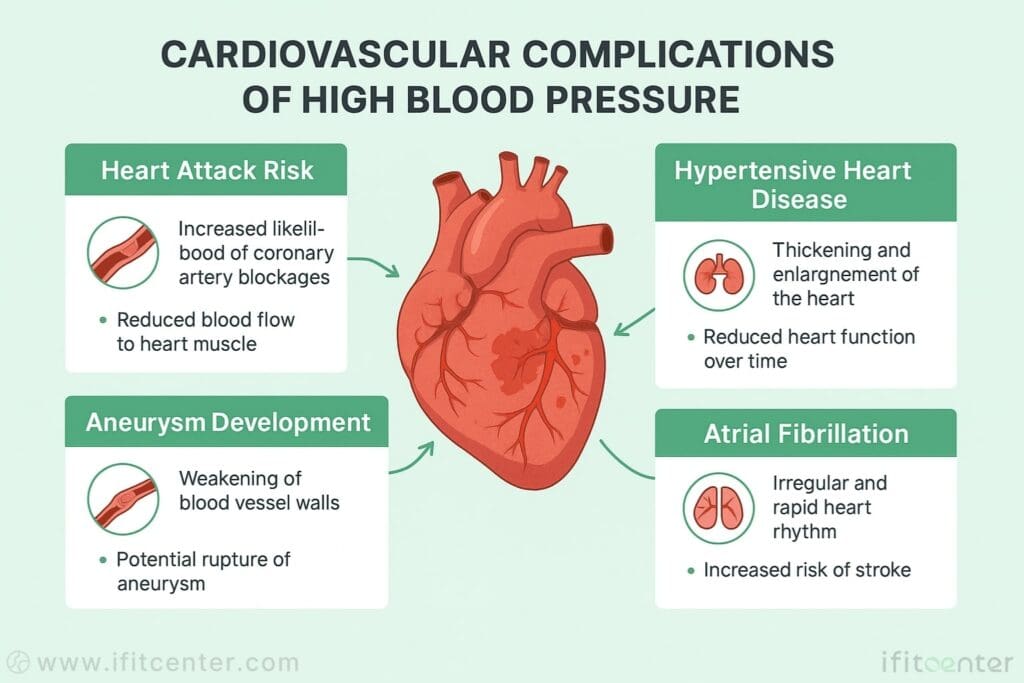

Cardiovascular Complications of High Blood Pressure

The heart and blood vessels bear the earliest and often most severe impact of hypertension. When blood pressure remains elevated, several serious cardiovascular complications can develop over time.

Heart Attack Risk and Hypertension

High blood pressure is a major contributor to heart attacks. Your heart muscle needs its own blood supply through coronary arteries that lie on top of the heart. These arteries aren’t just passive tubes—they’re living tissue that can be damaged by the constant force of high blood pressure.

When hypertension damages coronary arteries, it accelerates atherosclerosis—the buildup of plaque that narrows these critical vessels. As plaque accumulates, less blood reaches the heart muscle. If plaque ruptures or a blood clot forms, it can completely block blood flow to part of the heart, causing a heart attack.

The relationship between blood pressure and heart attack risk is direct and progressive. Even modest elevations in blood pressure significantly increase your risk. Research shows that young adults with blood pressure above normal but below the traditional hypertension threshold still face higher heart attack risk over time.

Complications of Hypertensive Heart Disease

When your blood pressure stays high, your heart must work harder to pump against increased resistance in your arteries. This extra workload causes the wall of the heart’s main pumping chamber (left ventricle) to thicken—a condition called left ventricular hypertrophy.

Think of it like a weightlifter’s muscles that grow larger with repeated stress. However, unlike skeletal muscles, this heart enlargement isn’t healthy. The thickened heart muscle becomes stiff and functions less efficiently. The heart chambers may eventually stretch and weaken, reducing the heart’s pumping ability.

This progression can lead to heart failure, where the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. Symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, and fluid retention. The risk of developing heart failure increases substantially with each increment of blood pressure above normal.

Aneurysm: A Serious Blood Pressure Complication

An aneurysm is a bulge in a weakened section of an artery wall, similar to a balloon forming on a weakened section of a garden hose. High blood pressure is a key factor in aneurysm development, as the constant force against artery walls can create these dangerous bulges.

Aneurysms can form in any artery but most commonly develop in:

- The aorta (the main artery leaving your heart)

- Brain arteries

- Arteries in the abdomen or legs

The danger of an aneurysm is that it can rupture without warning, causing life-threatening internal bleeding. A ruptured brain aneurysm can cause a hemorrhagic stroke, while a ruptured aortic aneurysm is a medical emergency with high mortality rates. Higher blood pressure levels directly increase both the risk of aneurysm formation and rupture.

Atrial Fibrillation and High Blood Pressure

Atrial fibrillation—an irregular, often rapid heart rhythm—is strongly linked to hypertension. When high blood pressure persists, it can cause structural changes in the heart’s upper chambers (atria), creating an environment where abnormal electrical signals can develop.

This remodeling process includes enlargement of the atria and the development of fibrosis (scarring) in heart tissue. These changes disrupt the heart’s normal electrical pathways, leading to the chaotic rhythm of atrial fibrillation.

The danger compounds when hypertension and atrial fibrillation occur together. Atrial fibrillation allows blood to pool in the heart chambers, potentially forming clots that can travel to the brain and cause a stroke. Research shows that people with both conditions have a substantially higher stroke risk than those with either condition alone.

A recent meta-analysis of 68 studies including over 30 million participants found that people with high blood pressure have a 50% higher risk of developing atrial fibrillation compared to those with normal blood pressure. The study also revealed that for each 20 mmHg increase in systolic blood pressure, the risk of atrial fibrillation increases by 18%.

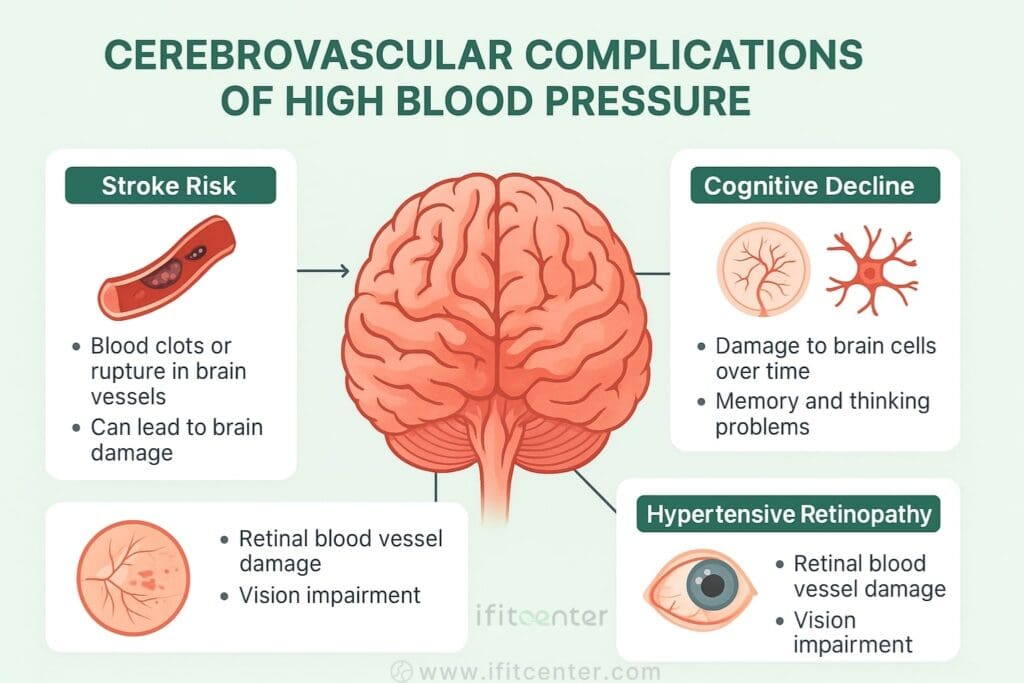

Cerebrovascular Complications of High Blood Pressure

Your brain depends on a constant supply of oxygen-rich blood to function properly. High blood pressure can severely damage the blood vessels that supply your brain, leading to several serious cerebrovascular complications.

Stroke Risk and High Blood Pressure

Stroke occurs when blood flow to part of the brain is interrupted, depriving brain cells of oxygen and nutrients. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic and hemorrhagic.

Ischemic strokes happen when a blood vessel supplying the brain becomes blocked, typically by a blood clot. These account for about 87% of all strokes. Hypertension contributes to ischemic strokes by accelerating atherosclerosis in cerebral arteries, creating environments where clots can form.

Hemorrhagic strokes occur when a weakened blood vessel ruptures, causing bleeding in or around the brain. These are less common but often more devastating. High blood pressure is the primary cause of hemorrhagic strokes, as it weakens arterial walls over time.

According a research study file, the relationship between blood pressure and stroke risk is strikingly clear. For each 10 mmHg increase in systolic blood pressure, stroke risk increases by 25%. For each 5 mmHg increase in diastolic blood pressure, stroke risk increases by 3%.

Even subtle elevations in blood pressure can affect cerebrovascular health over time. The study showed that people with “high-normal” blood pressure had a 14% higher stroke risk compared to those with optimal blood pressure.

Cognitive Decline and Hypertension

Recent research has revealed strong connections between hypertension and cognitive impairment, including Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. The references a significant meta-analysis that examined over 31,000 participants across 14 countries.

The study found that people with untreated high blood pressure were 36% more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease compared to those with normal blood pressure. Interestingly, those whose hypertension was properly treated showed no significant increase in Alzheimer’s risk compared to people with normal blood pressure.

Hypertension affects brain health through several mechanisms. It can cause small vessel disease, where tiny arteries deep in the brain narrow and block, leading to small, often unnoticed strokes. Over time, these “silent strokes” damage brain tissue and contribute to vascular dementia. High blood pressure also impairs the blood-brain barrier, allowing harmful substances to reach brain tissue.

The relationship appears to be dose-dependent—the higher the blood pressure and the longer it remains elevated, the greater the risk of cognitive decline.

“Many patients believe cognitive decline is only a concern with severe or long-standing hypertension, but this is a dangerous misconception. Even mild to moderate high blood pressure in your 40s and 50s can begin to affect brain function years before noticeable memory problems develop. The small vessels in the brain are particularly vulnerable to pressure-related damage, and this occurs silently well before symptoms appear. By the time someone notices memory issues, significant damage has already occurred. This is why I emphasize addressing elevated blood pressure early, regardless of age.”

Dr. Babak Jamalian, Family Physician.

Hypertensive Retinopathy

The eyes provide a unique window into how high blood pressure affects small blood vessels throughout your body. The retina—the light-sensitive layer at the back of your eye—contains tiny blood vessels that can be directly observed during an eye examination.

Hypertensive retinopathy develops when high blood pressure damages these delicate vessels. In early stages, the arteries may narrow and develop a “copper wire” or “silver wire” appearance as their walls thicken. As damage progresses, the vessels may leak fluid or blood, causing retinal swelling, hard exudates (protein deposits), or hemorrhages.

Ophthalmologists classify hypertensive retinopathy in four stages of increasing severity:

- Stage 1: Mild narrowing of the retinal arteries

- Stage 2: More severe narrowing, with areas of constriction and dilation

- Stage 3: Retinal hemorrhages, exudates, and cotton wool spots (areas of damaged nerve fibers)

- Stage 4: All of the above plus swelling of the optic nerve and macula (severe vision threat)

Early-stage retinopathy usually doesn’t cause symptoms, but advanced stages can lead to vision problems including blurred vision, vision loss, or even blindness. The presence of hypertensive retinopathy is also a warning sign that blood vessels in other organs—particularly the brain and kidneys—may be similarly damaged.

Regular eye examinations are valuable not only for detecting eye complications but also for assessing the overall impact of hypertension on your small blood vessels.

Kidney Complications of High Blood Pressure

Your kidneys play a vital role in filtering waste and excess fluid from your blood. These bean-shaped organs contain about a million tiny filtering units called nephrons, each with a cluster of blood vessels (glomerulus) that filter your blood. High blood pressure can severely damage these delicate structures.

Blood Pressure and Kidney Damage

When blood pressure is elevated, it forces the kidneys to work harder. Think of it like a filter processing water under too much pressure—eventually, the filter becomes damaged. The excessive pressure damages the nephrons’ blood vessels, reducing their ability to filter blood effectively.

What makes this relationship particularly dangerous is that it creates a harmful cycle. When kidney blood vessels are damaged by high blood pressure, the kidneys respond by releasing hormones that raise blood pressure even further. This creates a dangerous feedback loop where hypertension causes kidney damage, which then worsens hypertension.

On a microscopic level, high blood pressure thickens and narrows the kidney’s blood vessels. This reduces blood flow to kidney tissue and eventually leads to scarring that prevents normal function. The damage occurs gradually, often over many years.

According to studies, kidneys filter about 190 quarts of blood daily. With each increment of blood pressure above normal, this filtering capacity decreases. Elevated blood pressure is directly linked to a faster decline in kidney function over time.

Chronic Kidney Disease from Hypertension

Hypertension is the second leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide, after diabetes. CKD develops in stages, with kidney function gradually declining as damage accumulates.

The stages of kidney disease are primarily determined by how well the kidneys filter blood, measured by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). As hypertension continues to damage nephrons, GFR progressively declines. The earliest stages may show no symptoms at all, while advanced stages bring symptoms like fatigue, swelling, and changes in urination.

What makes kidney disease particularly dangerous is its silent progression. By the time symptoms appear, significant and often irreversible damage has already occurred. Laboratory tests are the only reliable way to detect early kidney disease, including:

- Blood tests measuring creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

- Urine tests looking for protein leakage (albuminuria)

- Imaging studies to assess kidney structure

hypertension accelerates kidney function decline. The risk increases with both the severity and duration of high blood pressure. There’s also a strong connection between kidney disease and other metabolic conditions like diabetes, obesity, and high cholesterol—all of which frequently occur alongside hypertension.

End-Stage Renal Disease and Hypertension

Without proper treatment, chronic kidney disease from hypertension can progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD)—complete or near-complete kidney failure. At this point, the kidneys can no longer keep up with waste removal and fluid balance, creating a life-threatening situation.

People with ESRD require kidney replacement therapy to survive. This means either:

- Dialysis: A mechanical filtering process that removes waste and excess fluid, typically needed 3 times weekly

- Kidney transplantation: Surgical placement of a healthy kidney from a donor

Both options significantly impact quality of life. Dialysis treatments are time-consuming and can cause fatigue and complications. Transplantation offers better quality of life but requires lifelong anti-rejection medications.

According to the resources, the risk of developing ESRD increases dramatically when blood pressure readings consistently exceed 140/90 mmHg. At blood pressure levels above 160/100 mmHg, the risk multiplies several times compared to those with normal blood pressure.

The relationship between kidney failure and hypertension isn’t just one-way. As kidney function declines, blood pressure typically becomes more difficult to control, creating a dangerous spiral of worsening health. This highlights why early detection and management of both conditions is crucial.

Complications of High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy

High blood pressure during pregnancy presents unique risks to both mother and baby. There are several hypertensive disorders specific to pregnancy that require careful attention and management.

To access the second section of blood pressure articles, I invite you to use the links below:

- dash diet to lower high blood pressure

- Best foods to lower blood pressure

- Foods to Avoid with High Blood Pressure

- Can Green Tea Lower Blood Pressure?

- Is coffee good for high blood pressure?

- What does a high blood pressure headache feel like

- obesity and hypertension statistics

- Controlling High Blood Pressure with Fasting

Preeclampsia Complications

Preeclampsia is a serious pregnancy complication characterized by high blood pressure and signs of damage to other organ systems, most often the liver and kidneys. It typically develops after 20 weeks of pregnancy, even in women who previously had normal blood pressure.

Diagnosis requires a blood pressure reading of 140/90 mmHg or higher, combined with protein in the urine (proteinuria) or other signs of organ damage. Some women also experience severe headaches, vision changes, upper abdominal pain, nausea, or shortness of breath.

Preeclampsia can lead to serious complications for both mother and baby. For the mother, these include:

- Eclampsia (seizures)

- HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count)

- Placental abruption (separation of the placenta from the uterine wall)

- Cardiovascular complications

- Organ damage, particularly to kidneys and liver

For the baby, preeclampsia can restrict growth due to decreased blood flow to the placenta, lead to preterm birth, or in severe cases, cause stillbirth.

According to a meta-analysis titled “Association between pre-existing or early pregnancy hypertension and pregnancy outcomes” that examined 23 cohort studies with over 4.5 million participants, women with preeclampsia have a 220% increased risk of adverse outcomes compared to women with normal blood pressure. This study, published in the Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, also found that even after pregnancy, women who experienced preeclampsia have a significantly higher risk of developing chronic hypertension and cardiovascular disease later in life.

Gestational Hypertension Complications

Gestational hypertension differs from preeclampsia in that it involves high blood pressure that develops after 20 weeks of pregnancy without the accompanying signs of organ damage. While often less severe than preeclampsia, it still requires careful monitoring.

Women with gestational hypertension face increased risks of:

- Progression to preeclampsia (about 25% of women with gestational hypertension develop preeclampsia)

- Induced labor or cesarean delivery

- Placental insufficiency leading to fetal growth restriction

- Preterm birth

The same meta-analysis found that gestational hypertension increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes by 156% compared to normotensive pregnancies. Even after delivery, blood pressure may not immediately return to normal. Women who experience gestational hypertension have a higher risk of developing chronic hypertension within 5-10 years after pregnancy.

Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy Complications

Chronic hypertension in pregnancy refers to high blood pressure that predates pregnancy or develops before 20 weeks gestation. Women with pre-existing hypertension face additional challenges during pregnancy.

The primary risks include:

- Superimposed preeclampsia (developing preeclampsia on top of existing hypertension)

- Fetal growth restriction

- Placental abruption

- Preterm delivery

- Higher rates of cesarean section

According to the meta-analysis from the Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, chronic hypertension during pregnancy increases the risk of adverse maternal outcomes by 190% and fetal complications by 101%. The study found that chronic hypertension affects the placenta by reducing uteroplacental blood flow, causing placental hypoxia and insufficient nutrient delivery to the developing fetus.

Long-term studies show that women with chronic hypertension during pregnancy have significantly higher cardiovascular risks throughout life, including increased rates of heart attack, stroke, and heart failure compared to women who maintained normal blood pressure during pregnancy.

Complications of Diabetes and Hypertension

When diabetes and hypertension occur together, they create a particularly dangerous combination. These two conditions frequently coexist—up to 75% of adults with diabetes also have hypertension—and they interact in ways that magnify damage throughout the body.

The Double Burden on Blood Vessels

Diabetes and hypertension each independently damage blood vessels, but together they create a synergistic effect that accelerates vascular disease. This combination has been aptly described as “the deadly duo” in medical literature.

Diabetes affects blood vessels by:

- Causing endothelial dysfunction (damage to the inner lining of blood vessels)

- Promoting inflammation in vessel walls

- Reducing nitric oxide production (which normally helps vessels dilate)

- Increasing oxidative stress (cell damage from free radicals)

- Creating advanced glycation end products (AGEs) that damage vessel proteins

When high blood pressure is added to this mix, it amplifies the damage by applying mechanical stress to already compromised vessels. The combination leads to faster progression of atherosclerosis, vessel stiffening, and reduced blood flow to vital organs.

A study examining the combined effects of these conditions found that people with both diabetes and hypertension have approximately twice the risk of cardiovascular events compared to those with either condition alone. The vascular aging process—normally occurring gradually over decades—accelerates dramatically when these conditions coexist.

Unique Complications When Both Conditions Coexist

Several complications become particularly prominent when diabetes and hypertension occur together:

Accelerated Diabetic Nephropathy: While both conditions independently damage kidneys, their combination dramatically speeds kidney function decline. Hypertension damages the kidneys’ filtering units, while diabetes impairs the small blood vessels that supply them. Together, they can lead to diabetic nephropathy progressing to end-stage renal disease much faster than either condition alone.

Enhanced Retinopathy Risk: Both diabetes and hypertension cause retinal damage, but their combination substantially increases the risk of vision loss. Diabetes damages the small blood vessels in the retina, while hypertension applies increased pressure to these already compromised vessels. The result is accelerated retinopathy progression and higher rates of vision impairment.

Increased Peripheral Artery Disease: The combination dramatically increases the risk of peripheral artery disease (PAD), where narrowed arteries reduce blood flow to the limbs. This can cause pain with walking (claudication) and, in severe cases, tissue death that may require amputation.

Heightened Cardiovascular Mortality: Heart attacks, strokes, and heart failure occur with greater frequency and severity when both conditions are present. A large-scale study titled “Hypertension and Diabetes: The Double-Edged Sword of Cardiovascular Risk” found that the 10-year risk of a fatal cardiovascular event is approximately three times higher in people with both conditions compared to those with neither, even after accounting for other risk factors.

What makes this combination particularly concerning is that the effects are more than additive—they are multiplicative. Each condition worsens the other, with diabetes making blood pressure more difficult to control, and hypertension worsening insulin resistance and glycemic control. This creates a negative feedback loop that accelerates organ damage throughout the body.

High Diastolic Blood Pressure Complications

While much attention focuses on systolic blood pressure (the top number), diastolic pressure (the bottom number) can cause its own set of serious complications. Understanding these risks is essential for comprehensive blood pressure management.

Understanding Isolated Diastolic Hypertension

Isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH) occurs when diastolic blood pressure is elevated (80 mmHg or higher) while systolic pressure remains normal (less than 130 mmHg). This condition represents the pressure in your arteries when your heart is between beats, essentially the minimum pressure your blood vessels experience.

Diastolic pressure is particularly important because it indicates how much resistance your small arteries are creating as blood flows through them. When diastolic pressure is consistently high, it suggests these small arteries have become stiff and narrow, forcing your heart to work harder to push blood through the circulatory system.

Interestingly, isolated diastolic hypertension shows different age-related patterns than systolic hypertension. It’s more common in younger adults under 50, while isolated systolic hypertension becomes more prevalent in older adults. This pattern relates to different underlying causes—in younger people, high diastolic pressure often stems from increased peripheral resistance in small arteries, while in older adults, stiff large arteries contribute more to systolic elevation.

According to the study “Association between high blood pressure and long-term cardiovascular events in young adults,” published in PMC, high diastolic blood pressure in young adults carries its own distinct risk profile. The study found that for each 10 mmHg increase in diastolic blood pressure, the risk of cardiovascular events increased by 18%, heart disease by 2%, and stroke by 3%.

Organ Damage Specific to High Diastolic Blood Pressure

Elevated diastolic blood pressure affects various organ systems, sometimes in ways that differ from systolic hypertension:

Cardiovascular Implications: High diastolic pressure particularly impacts coronary artery perfusion. Since the heart receives most of its blood supply during diastole (when the heart muscle relaxes), elevated diastolic pressure can reduce coronary blood flow and oxygen delivery to the heart. This increases the risk of myocardial ischemia (insufficient blood flow to heart tissue) and can accelerate the development of coronary artery disease.

Renal Effects: The kidneys are sensitive to changes in diastolic pressure. Persistently elevated diastolic pressure can damage the small blood vessels within the kidneys, impairing their filtering function. According to data from long-term studies, diastolic hypertension may predict kidney function decline in some populations even better than systolic hypertension does.

Cerebrovascular Risks: High diastolic pressure creates significant strain on the small, delicate vessels in the brain. Research in the “Blood pressure, hypertension, and risk of atrial fibrillation” study showed that elevated diastolic pressure has a non-linear relationship with stroke risk—meaning even moderate increases can substantially raise the danger of both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.

Complications of Uncontrolled Hypertension

When hypertension remains untreated or poorly controlled, the pace and severity of complications accelerate significantly. Understanding the consequences of uncontrolled high blood pressure highlights the critical importance of consistent blood pressure management.

Accelerated Organ Damage Timeline

Uncontrolled hypertension speeds up damage to multiple organ systems simultaneously. While controlled hypertension can cause gradual changes over decades, severe uncontrolled blood pressure can produce noticeable organ damage within just a few years.

The acceleration happens because persistently high blood pressure creates a cascade of harmful effects. Blood vessels throughout the body rapidly lose elasticity and develop atherosclerotic plaques. As these vessels narrow and stiffen, blood flow to vital organs decreases, triggering compensatory mechanisms that further raise blood pressure and damage organs.

With uncontrolled hypertension, multiple organ systems face simultaneous damage:

- Heart: Accelerated left ventricular hypertrophy leading to heart failure

- Brain: Increased risk of stroke, vascular dementia, and cognitive decline

- Kidneys: Rapid loss of kidney function progressing toward kidney failure

- Eyes: Progressive retinopathy with potential vision loss

- Blood vessels: Widespread atherosclerosis and increased aneurysm risk

This multisystem damage significantly impacts quality of life. Patients often experience fatigue, reduced exercise capacity, cognitive changes, and limitations in daily activities. According to the research highlighted in “Clinical outcomes in hypertensive emergencies” published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, severe uncontrolled hypertension can substantially reduce life expectancy compared to those with well-controlled blood pressure.

Resistant Hypertension and Enhanced Complication Risk

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that remains above goal despite treatment with three or more antihypertensive medications (including a diuretic) at optimal doses, or blood pressure that requires four or more medications to achieve control.

This condition affects approximately 10-20% of people with hypertension and presents particularly serious risks. Patients with resistant hypertension experience a significantly higher rate of complications because their blood pressure remains elevated despite multiple medications.

According to the study “Heart failure risk in ambulatory resistant hypertension” published in Nature’s Hypertension Research journal, patients with ambulatory resistant hypertension (ARH) face substantial additional risks. The study examined 21,365 patients and found that those with resistant hypertension had 2.32 times higher risk of developing heart failure compared to those with controlled hypertension.

Resistant hypertension accelerates organ damage through several mechanisms:

- Consistently higher blood pressure levels (often 20+ mmHg higher than in controlled hypertension)

- Greater variability in blood pressure, with frequent spikes

- Longer duration of exposure to high blood pressure

- Often associated with other conditions like sleep apnea, obesity, or kidney disease that compound damage

Complications of Hypertensive Crisis

A hypertensive crisis represents the most severe and acute form of high blood pressure, requiring immediate medical attention. Understanding the different types of hypertensive crisis and their potential complications is essential for recognizing this dangerous condition.

Hypertensive Urgency vs. Emergency Complications

Hypertensive crisis is defined as blood pressure readings above 180/120 mmHg. Medical professionals divide these crises into two categories based on the presence of organ damage:

Hypertensive urgency occurs when blood pressure is severely elevated but hasn’t yet caused acute damage to target organs. Patients may experience symptoms such as severe headache, shortness of breath, or nosebleeds, but without immediate evidence of organ damage. While still serious, hypertensive urgency allows for blood pressure reduction over hours rather than minutes.

Hypertensive emergency is more dangerous, characterized by extremely high blood pressure with evidence of acute damage to target organs. This requires immediate hospitalization and rapid blood pressure reduction to prevent further organ damage or death.

According to “Clinical outcomes in hypertensive emergencies” published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, hypertensive emergencies account for approximately 1-2% of all hypertensive patients. However, among patients who present to emergency departments with blood pressure crises, approximately 24-68% have evidence of acute organ damage, qualifying as true hypertensive emergencies.

Risk stratification depends on several factors including the rate of blood pressure rise, previous hypertension history, and pre-existing conditions. Patients with a history of kidney disease, heart failure, or previous hypertensive crises face particularly high risks during these events.

Organ Damage in Hypertensive Emergency

Extremely high blood pressure can cause rapid and severe damage to multiple organ systems:

Brain Complications: Hypertensive encephalopathy develops when severely elevated blood pressure overcomes the brain’s autoregulatory mechanisms, causing cerebral edema (brain swelling). Symptoms include altered mental status, seizures, and coma. Hypertensive emergency also significantly increases the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, where blood vessels in the brain rupture under extreme pressure.

Heart Complications: The heart faces enormous strain during hypertensive crisis. Acute heart failure can develop as the heart struggles to pump against extremely high resistance. Myocardial ischemia or infarction (heart attack) may occur as the heart’s oxygen demand exceeds supply.

Kidney Complications: Hypertensive emergency can cause acute kidney injury through a process called malignant nephrosclerosis. The extreme pressure damages the kidney’s small blood vessels, reducing blood flow to nephrons and causing rapid deterioration in kidney function. This may manifest as reduced urine output, elevated creatinine levels, and proteinuria (protein in urine).

Eye Complications: The retina provides a direct window to blood vessel damage during hypertensive crisis. Severe acute hypertension can cause papilledema (swelling of the optic nerve), retinal hemorrhages, exudates, and even retinal detachment. These changes can lead to sudden vision disturbances or vision loss that may become permanent without prompt treatment.

According to the analysis of hypertensive emergencies, the mortality rate during hospitalization for hypertensive emergency is approximately 9.9%. This underscores the life-threatening nature of this condition and the importance of immediate intervention.

Long-term Consequences After Hypertensive Crisis

Even after survival and stabilization, patients who experience a hypertensive crisis face ongoing health challenges:

Risk of Recurrence: Once a person experiences a hypertensive crisis, they have a significantly higher risk of experiencing another.

Accelerated Organ Damage: Even after blood pressure is controlled, the extreme strain experienced during crisis accelerates long-term damage to blood vessels and organs. Patients who survive hypertensive emergencies show faster progression of atherosclerosis and organ dysfunction than those with similar baseline blood pressure who haven’t experienced a crisis.

Permanent Functional Deficits: Depending on which organs were affected during the crisis, patients may experience long-term or permanent functional impairments. These can include neurological deficits after brain involvement, reduced kidney function, heart failure, or vision impairment.

Other Health Problems Caused by High Blood Pressure

Beyond the major complications already discussed, high blood pressure can cause several additional health problems that significantly impact quality of life. These conditions often receive less attention but can be just as debilitating for those affected.

Peripheral Artery Disease

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) develops when narrowed arteries reduce blood flow to the limbs, most commonly the legs. High blood pressure is a major contributor to this condition.

PAD develops through a similar process to coronary artery disease. High blood pressure damages the arterial walls, accelerating atherosclerosis (plaque buildup) in the peripheral arteries. As these vessels narrow, less blood reaches the legs and feet, causing symptoms and eventually tissue damage.

The classic symptom of PAD is claudication—pain, cramping, or tiredness in the leg muscles that occurs during activity and improves with rest. As the condition progresses, symptoms may include:

- Leg pain even at rest

- Numbness or weakness in the legs

- Coolness in the lower leg or foot

- Sores that won’t heal on the toes, feet, or legs

- Change in leg color or shiny skin on the legs

- Hair loss or slower hair growth on affected limbs

PAD also serves as a marker for widespread atherosclerosis throughout the body. People with PAD have a significantly higher risk of heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular death compared to those without the condition.

Sexual Dysfunction

The link between high blood pressure and sexual dysfunction often goes undiscussed, yet it represents a significant quality of life issue for many people with hypertension.

In men, erectile dysfunction (ED) is closely linked to hypertension. Healthy erections require adequate blood flow to the penis, and high blood pressure damages the arteries that supply this blood. As these vessels narrow and lose elasticity, achieving and maintaining erections becomes more difficult.

The connection works through several mechanisms:

- Endothelial dysfunction: The same damage to blood vessel linings that occurs throughout the body affects the penile arteries

- Reduced nitric oxide: Hypertension decreases production of nitric oxide, a molecule crucial for the relaxation of blood vessels during erection

- Structural changes: Long-term hypertension causes structural changes in the penile tissue itself

Conclusion

High blood pressure truly deserves its reputation as the “silent killer.” As we’ve explored throughout this article, hypertension can damage virtually every major organ system in the body, often without causing noticeable symptoms until significant harm has occurred.

The complications of high blood pressure are extensive and serious. Cardiovascular effects include heart attack, heart failure, aneurysms, and atrial fibrillation. Brain complications range from stroke to cognitive decline and dementia. Kidney damage can progress to complete kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation. During pregnancy, hypertension threatens both maternal and fetal health through conditions like preeclampsia.

What makes these complications particularly concerning is their progressive nature. Blood pressure-related damage accumulates gradually over years or decades. Each increment of blood pressure above normal increases risk, and the longer blood pressure remains elevated, the greater the potential harm.

To access other content on the IFitCenter’s blog, you can use the following links:

References

- Coccina, F., Salles, G. F., Banegas, J. R., Hermida, R. C., Bastos, J. M., Cardoso, C. R. L., Salles, G. C., Sánchez-Martínez, M., Mojón, A., Fernández, J. R., Costa, C., Carvalho, S., Faia, J., & Pierdomenico, S. D. (2024). Risk of heart failure in ambulatory resistant hypertension: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Hypertension Research, 47, 1235-1245. DOI: 10.1038/s41440-024-01463-71

- Siddiqui, T. J., Usman, M. S., Rashid, A. M., Javaid, S. S., Ahmed, A., Clark, D. III, Flack, J. M., Shimbo, D., Choi, E., Jones, D. W., & Hall, M. E. (2023). Clinical Outcomes in Hypertensive Emergency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association, 12(14). DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.122.0293552

- Peng, X., Jin, C., Song, Q., Wu, S., & Cai, J. (2023). Stage 1 Hypertension and the 10-Year and Lifetime Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Real-World Study. Journal of the American Heart Association, 12(7). DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.122.0287623

- Gallo, G., Volpe, M., & Savoia, C. (2022). Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertension: Current Concepts and Clinical Implications. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 798958. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2021.798958

- Rocha Carvalho, P., Moreira, I., Carvalho, C., Bernardo, M., Monteiro, J., Fontes, P., & Moreira, J. I. (2022). The diastolic blood pressure U-curve. European Heart Journal, 43(Supplement_2), ehac544.2228. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac544.22281

- Otto, C. M. (2018). Heartbeat: commuting and cardiovascular health. Heart, 104, 1725-1726. DOI: not provided in image2

- Bramham, K., Parnell, B., Nelson-Piercy, C., Seed, P. T., Poston, L., & Chappell, L. C. (2014). Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 348, g2301. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.g23013

- Giunti, S., Barit, D., & Cooper, M. E. (2006). Mechanisms of Diabetic Nephropathy: Role of Hypertension. Hypertension, 48(4). DOI: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000240331.32352.0c

- Abegaz, T. M., Tefera, Y. G., & Abebe, T. B. (2017). Target Organ Damage and the Long Term Effect of Nonadherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines in Patients with Hypertension: A Retrospective Cohort Study. International Journal of Hypertension, 2017. DOI: 10.1155/2017/26370511

- Wu, D., Gao, L., Huang, O., Ullah, K., Guo, M., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Chen, L., Fan, J., Sheng, J., Lin, X., & Huang, H. (2020). Increased Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Associated With Stage 1 Hypertension in a Low-Risk Cohort: Evidence From 47 874 Cases. Hypertension, 75(3). DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14252

- Lawes, C. M. M., Bennett, D. A., Feigin, V. L., & Rodgers, A. (2004). Blood Pressure and Stroke: An Overview of Published Reviews. Stroke, 35(3). DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.0000116869.64771.5A

- Bidani, A. K., & Griffin, K. A. (2004). Pathophysiology of Hypertensive Renal Damage: Implications for Therapy. Hypertension, 44(5). DOI: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145180.38707.84