Did you know that for every 5-unit increase in BMI, your risk of developing type 2 diabetes increases by a staggering 72%? Or that carrying excess weight around your waist makes you nearly twice as likely to develop diabetes compared to carrying weight elsewhere on your body?

Have you ever wondered why some people with obesity never develop diabetes while others do? Or why central obesity—that apple-shaped body pattern—presents a particularly high risk? The relationship between obesity and type 2 diabetes has become so intertwined that medical researchers now use the term “diabesity” to describe this dangerous connection.

These questions matter because understanding your personal risk goes far beyond just stepping on a scale. At IFitCenter Clinic, we’ll explore the precise mechanisms that link excess body fat to insulin resistance and diabetes, revealing why waist circumference might matter more than your overall weight, and what specific steps can help break this cycle before diabetes develops.

Whether you’re concerned about your own risk or trying to support a loved one, this comprehensive guide will provide the evidence-based insights you need to understand how obesity influences diabetes development—and what you can do about it today.

Understanding How does Obesity Cause Diabetes

The global rates of both obesity and diabetes have risen dramatically over recent decades. According to the International Diabetes Federation, 537 million adults (10.5% of global population) lived with diabetes in 2021, projected to reach 783 million by 2045. Meanwhile, obesity rates have nearly tripled worldwide since 1975.

What is “Diabesity”?

Medical professionals have coined the term “diabesity” to describe the close relationship between diabetes and obesity. This term highlights how frequently these conditions occur together and their shared biological pathways. While not everyone with obesity develops diabetes, the overlap is significant enough to warrant special attention.

How Excess Fat Leads to Insulin Resistance

Insulin works like a key that unlocks your cells, allowing glucose (sugar) from your bloodstream to enter and provide energy. When you develop insulin resistance, insulin can’t work effectively, leaving glucose circulating in your bloodstream. Your pancreas then produces more insulin to compensate, creating a cycle that can eventually lead to diabetes.

Research clearly shows that as your weight increases, so does your diabetes risk. A 2022 study in the British Medical Journal found that for every 5-unit increase in BMI, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes jumps by 72%. This means moving from a BMI of 25 (overweight) to 30 (obese) increases your diabetes risk by nearly three-quarters.

Most importantly, this relationship is linear—there is no “safe threshold” where risk suddenly increases. Each pound gained progressively raises your diabetes risk, beginning well before reaching clinical obesity.

Why Waist Size Matters More Than Weight

Not all body fat increases diabetes risk equally. Where you carry your weight matters tremendously. Central obesity—excess fat around your midsection—poses a much greater threat than fat stored in other areas like hips and thighs.

Your waist-to-height ratio has emerged as one of the strongest predictors of diabetes risk, often more accurate than BMI. A ratio of 0.5 or greater (meaning your waist circumference is more than half your height) significantly increases your risk of developing diabetes.

To calculate this ratio, simply divide your waist circumference by your height (using the same units). For example, if you’re 5’6″ (66 inches) tall with a 36-inch waist, your ratio would be 0.55—indicating elevated risk.

“What many patients don’t realize is that waist-to-height ratio is often more predictive of diabetes risk than BMI alone. I’ve observed that individuals with a ratio above 0.5—meaning their waist circumference exceeds half their height—consistently show earlier signs of insulin resistance, even when their overall weight appears only moderately elevated. This simple measurement provides a more accurate assessment of metabolically active visceral fat, which directly impacts glucose metabolism.”

Dr. Babak Jamalian, Family Physician.

Reduce Your Waistline, Lower Your Diabetes Risk

Carrying excess weight around your waist significantly raises your risk of developing type 2 diabetes due to the harmful effects of visceral fat. Fortunately, targeted weight loss, especially from the midsection, can greatly enhance insulin sensitivity and reduce this risk.

At iFitCenter, we offer medically supervised weight-loss programs specifically aimed at reducing harmful visceral fat. Using comprehensive metabolic evaluations and personalized nutritional guidance, we create practical plans that support sustainable weight loss and better metabolic health.

Your journey to a healthier waistline—and reduced diabetes risk—can start today.

Visceral Fat: The Dangerous Fat You Can’t See

To understand why central obesity is so harmful, we need to examine the different types of fat in your body. Fat just beneath the skin (subcutaneous fat) behaves very differently than fat surrounding internal organs (visceral fat).

Visceral fat is metabolically active—think of it as an organ that produces hormones and inflammatory substances. These substances travel directly to your liver through the portal vein, interfering with your body’s insulin signaling and glucose regulation.

How Fat Tissue Becomes Dysfunctional

In obesity, fat cells enlarge beyond their healthy size. These oversized cells often receive inadequate blood supply, leading to low oxygen levels (hypoxia). This triggers inflammation as immune cells called macrophages infiltrate the tissue.

These immune cells release inflammatory proteins that interfere with insulin signaling throughout your body, driving insulin resistance. It’s like static disrupting a clear radio signal—insulin is present, but the cells can’t properly receive its message.

On the IFitCenter blog, we have provided a comprehensive guide for diabetes, completely free of charge and based on the latest research. By viewing these articles, in addition to increasing your general knowledge in this field, you can easily manage this disease in a principled manner. To access the first part of the articles, simply use the links below:

- What is Diabetes?

- Symptoms and Signs of Diabetes

- Difference Between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes

- What Are the Complications of Diabetes?

- Diabetes Diagnosis Method

- What are 5 Ways to Prevent Diabetes?

How Excess Fat Affects Your Liver

Your liver plays a crucial role in regulating blood glucose levels. When exposed to inflammatory signals from visceral fat, your liver becomes resistant to insulin’s signal to stop producing glucose. This leads to excess glucose production even when blood levels are already high.

Additionally, fat begins accumulating in the liver itself—a condition called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—which further impairs liver function and insulin sensitivity.

Fat in the Wrong Places: Ectopic Fat Deposition

When your body’s fat storage capacity is overwhelmed, fat begins accumulating in tissues not designed for significant fat storage—a process called ectopic fat deposition. This affects your:

- Liver: Impairing its ability to regulate blood sugar

- Muscles: Interfering with glucose uptake

- Pancreas: Potentially damaging insulin-producing beta cells

This helps explain why targeted reduction of visceral fat can dramatically improve metabolic health, even with modest overall weight loss.

Identifying Your Diabetes Risk Factors and Obesity

Critical Measurements for Assessing Type 2 Diabetes Risk

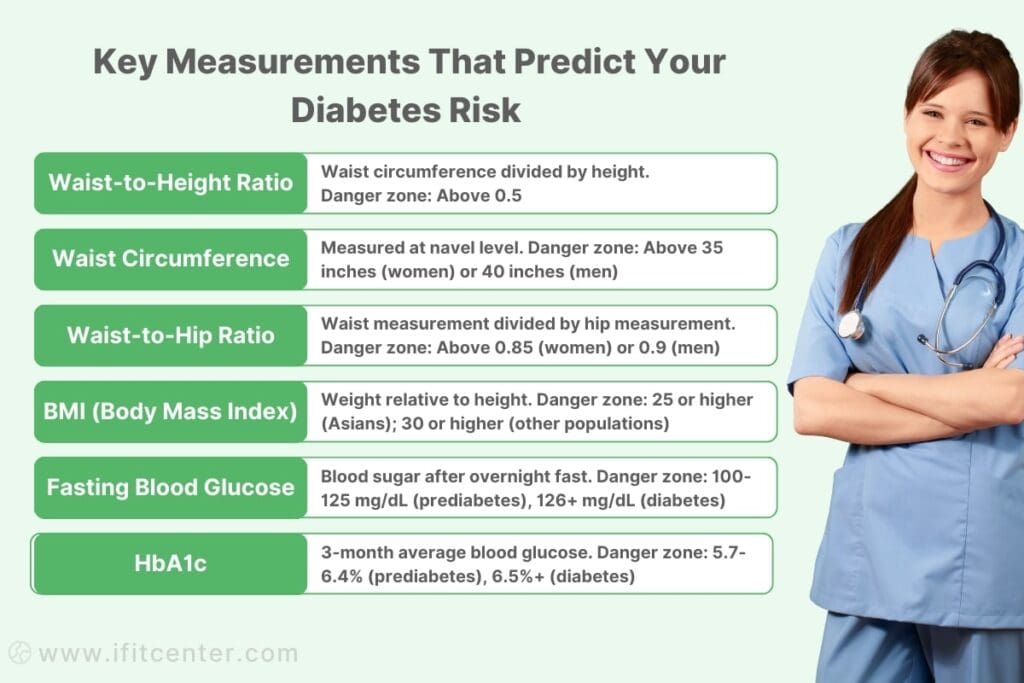

While BMI provides a general assessment of weight status, more specific measurements offer better insight into your diabetes risk. These measurements focus on where fat is distributed rather than just how much you have.

- Waist circumference: Measure around your natural waistline, typically at the level of your navel. For women, a measurement over 35 inches (88 cm) indicates increased risk. For men, the threshold is 40 inches (102 cm).

- Waist-to-height ratio: Divide your waist circumference by your height. A ratio above 0.5 indicates elevated risk regardless of your gender or ethnic background.

- Waist-to-hip ratio: Divide your waist measurement by your hip measurement. Ratios above 0.9 for men and 0.85 for women suggest higher risk.

Of these measurements, waist-to-height ratio has emerged as particularly valuable because it works consistently across different height ranges and ethnic groups.

When Obesity Combines With Other Risk Factors

Obesity increases diabetes risk on its own, but when combined with other risk factors, the danger multiplies. Pay particular attention if you have:

- Family history: Having a first-degree relative (parent or sibling) with type 2 diabetes increases your risk significantly. If both parents have diabetes, your risk is even higher.

- Age: Risk increases after age 45, though type 2 diabetes is increasingly diagnosed in younger adults and even children when obesity is present.

- Ethnicity: People of certain ethnic backgrounds including South Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Hispanic, and African American heritage have higher diabetes risk at lower weight thresholds.

- History of gestational diabetes: Women who developed diabetes during pregnancy face a substantially higher lifetime risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Research shows that having both obesity and a family history of diabetes creates greater risk than would be expected from these factors individually—they have a synergistic effect.

Obesity and Diabetes Risk Across Different Populations

The relationship between obesity and type 2 diabetes varies significantly across different population groups. Some key variations include:

- Asian populations: Develop diabetes at significantly lower BMI thresholds compared to Western populations. This has led to the development of Asia-specific BMI cutoffs that define obesity at BMI ≥25 kg/m² rather than ≥30 kg/m².

- Age differences: Younger adults with obesity face relatively higher diabetes risk compared to older adults with the same BMI.

- Gender variations: Women with obesity have a stronger relative risk of developing diabetes compared to men with obesity.

These variations highlight why personalized risk assessment is essential rather than relying solely on general population guidelines.

Signs Your Body May Be Developing Insulin Resistance

Before diabetes develops, your body often shows subtle signs of insulin resistance. Being aware of these early warning signals can help you take action sooner:

- Acanthosis nigricans: Dark, velvety patches of skin typically appearing on the neck, armpits, or groin. This skin change directly relates to insulin resistance as high insulin levels stimulate skin cell growth in these areas.

- Skin tags: Multiple small flesh-colored growths, especially on the neck and armpits, are linked to insulin resistance.

- Central weight gain: Increasing waist size, particularly if other parts of your body remain relatively unchanged.

- Difficulty losing weight: Insulin resistance makes weight loss more challenging, creating a frustrating cycle.

- Fatigue after meals: Feeling extremely tired after eating carbohydrate-rich foods.

- Increased hunger and cravings: Particularly for sweet or starchy foods.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): For women, this condition commonly co-occurs with insulin resistance.

Evidence-Based Approaches to Breaking the Obesity-Diabetes Cycle

Understanding the connection between obesity and type 2 diabetes is important, but knowing how to effectively intervene is even more crucial. Research has identified several strategies that specifically target insulin resistance and can help prevent or even reverse diabetes progression.

To access the second part of the articles related to diabetes, you can use the following links:

- Is Diabetes Curable?

- Type 2 Diabetes Explained

- Type 1 Diabetes Explained

- Causes of Diabetes

- Understanding Blood Sugar Numbers

- Which vinegar is best for diabetics

Dietary Approaches That Improve Insulin Sensitivity

Not all eating patterns affect insulin resistance equally. Research has identified specific dietary approaches that can significantly improve how your body responds to insulin:

- Mediterranean diet: Rich in olive oil, nuts, fish, and vegetables, this eating pattern has consistently shown benefits for insulin sensitivity. The combination of healthy fats and anti-inflammatory compounds appears particularly effective.

- Lower carbohydrate approaches: Reducing carbohydrate intake, particularly refined carbohydrates and added sugars, can significantly improve glucose metabolism even without substantial weight loss.

- Higher fiber intake: Foods rich in soluble fiber slow glucose absorption and improve insulin sensitivity. Aim for 20-30g of fiber daily from vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains.

- Meal timing: Some research indicates that eating meals earlier in the day and maintaining consistent meal timing helps optimize insulin function.

The quality of carbohydrates matters as much as the quantity. Focusing on unprocessed, high-fiber sources while limiting refined carbohydrates can improve metabolic health even when total carbohydrate intake remains similar.

How Exercise Improves Insulin Sensitivity

Physical activity has a powerful effect on insulin sensitivity that operates through multiple mechanisms:

- Exercise stimulates glucose uptake by muscles independently of insulin

- Regular activity increases the number and efficiency of glucose transporters in muscle cells

- Physical activity reduces inflammatory markers that contribute to insulin resistance

- Exercise enhances mitochondrial function, improving cellular energy metabolism

Importantly, these benefits occur even without significant weight loss. A single exercise session can improve insulin sensitivity for 24-48 hours, while consistent activity creates lasting improvements in glucose metabolism.

Optimal Activity Types for Metabolic Health

Research has identified specific exercise patterns that provide the greatest benefits for insulin sensitivity and diabetes prevention:

- Resistance training: A meta-analysis revealed optimal parameters include 2-3 weekly sessions at 70-80% of maximum capacity, performing 3 sets of 8-10 repetitions per exercise with short rest intervals.

- Aerobic exercise: Aim for 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity weekly, or 75 minutes of vigorous activity.

- Combined approaches: Integrating both resistance and aerobic exercise appears more effective than either alone.

- Walking pace: Walking speed matters significantly. Research shows brisk walking (>6.4 km/hour) reduces diabetes risk by 39% compared to casual walking.

- Daily movement: Breaking up sitting time with short movement breaks helps maintain insulin sensitivity throughout the day.

Even modest increases in physical activity can yield significant benefits. The relationship between activity and diabetes risk follows a dose-response pattern, with each incremental increase in activity providing additional protection.

“The most encouraging aspect of current diabetes research is that metabolic improvements often precede significant weight loss. Many of my patients see normalized blood glucose levels after losing just 5-7% of their initial weight, particularly when that weight loss comes from the abdominal region. This challenges the misconception that you need to reach an ‘ideal’ weight to improve your metabolic health—modest, sustainable changes often yield remarkable results when approached systematically.”

Dr. Babak Jamalian, Family Physician.

The Possibility of Diabetes Remission

Perhaps the most exciting development in diabetes research is the growing evidence that type 2 diabetes can actually be reversed in many cases. This concept, known as diabetes remission, involves reducing blood glucose to non-diabetic levels without medication.

Landmark studies like the DiRECT trial have demonstrated that significant weight loss can lead to remission of type 2 diabetes, particularly when intervention occurs within the first 6 years after diagnosis. The primary findings suggest:

- Weight loss of 15kg or more offers the highest likelihood of remission

- Even losing 5-10kg significantly improves glucose control

- The mechanism involves reducing fat in the liver and pancreas, restoring beta-cell function

- Earlier intervention yields higher success rates

The threshold for improvement appears to be losing approximately 5-7% of body weight, with progressively greater benefits as weight loss increases. This explains why approaches that achieve substantial weight loss, such as bariatric surgery, show such impressive diabetes remission rates.

What makes this particularly encouraging is that the improvements in glucose metabolism often occur early in the weight loss process, with many people seeing significant benefits within weeks of starting an effective program.

Successfully maintaining these changes often requires a comprehensive approach addressing diet, physical activity, sleep, stress management, and sometimes medication. Working with healthcare professionals who specialize in metabolic health can help develop a personalized plan based on your specific needs, preferences, and medical history. This integrated approach offers the best chance of not just breaking the obesity-diabetes cycle temporarily, but creating sustainable long-term improvements in metabolic health.

Summary: Obesity and Diabetes Correlation

The relationship between obesity and diabetes is complex but clear. While obesity increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes primarily, understanding this connection provides powerful opportunities for prevention and management.

The Obesity-Diabetes Connection Simplified

At its core, excess body fat—especially around your midsection—creates inflammation and disrupts normal insulin function. This leads to insulin resistance, where your body’s cells don’t respond properly to insulin. Your pancreas works harder to produce more insulin, eventually becoming exhausted. This progression from insulin resistance to diabetes can be interrupted through targeted interventions.

Know Your Personal Risk Profile

Your individual risk depends on more than just weight. Pay attention to:

- Waist-to-height ratio (keep below 0.5)

- Family history of diabetes

- Ethnicity (some groups face higher risk)

- Early warning signs like skin changes

- Prediabetes indicators

Small Weight Loss, Big Health Gains

You don’t need to reach an “ideal” weight to see significant health improvements. Research consistently shows that modest weight reduction—just 5-7% of your current weight—can dramatically reduce diabetes risk. For someone weighing 200 pounds, that’s just 10-14 pounds. Focus on progress, not perfection.

Focus on Metabolic Health, Not Just Weight

The scale doesn’t tell the whole story. Improvements in insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels often occur before significant weight loss appears. Regular physical activity improves metabolic health regardless of weight changes. The quality of your diet matters as much as the quantity of food you eat.

Early Action Creates the Best Results

The earlier you address insulin resistance, the better your outcomes. Research shows higher remission rates when intervention occurs within the first few years after diagnosis. Don’t wait for diabetes to develop—addressing obesity and insulin resistance during the prediabetes stage is significantly more effective.

Successfully breaking the obesity-type 2 diabetes cycle often requires personalized approaches. Consulting with healthcare professionals who specialize in metabolic health can help you develop strategies tailored to your unique situation, addressing your specific metabolic profile, preferences, and circumstances. This personalized approach increases your chances of both short-term success and long-term health improvements.

To access other content on the IFitCenter’s blog, you can use the following links:

References for How does Obesity Cause Diabetes

- Ali, S., Hussain, R., Malik, R. A., Amin, R., & Tariq, M. N. (2024). Association of Obesity With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Hospital-Based Unmatched Case-Control Study. Cureus, 16(1), e52728. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.52728

- Chandrasekaran, P., & Weiskirchen, R. (2024). The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—An Overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(3), 1882. DOI: 10.3390/ijms25031882

- Cao, C., Hu, H., Zheng, X., et al. (2022). Association between central obesity and incident diabetes mellitus among Japanese: a retrospective cohort study using propensity score matching. Scientific Reports, 12, 13445. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-17837-1

- Maula, A., Kai, J., Woolley, A. K., Weng, S., Dhalwani, N., Griffiths, F. E., Khunti, K., & Kendrick, D. (2019). Educational weight loss interventions in obese and overweight adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetic Medicine, 36(12), 1620–1632. DOI: 10.1111/dme.14193

- He, Q.-X., Zhao, L., Tong, J.-S., Liang, X.-Y., Li, R.-N., Zhang, P., & Liang, X.-H. (2022). The impact of obesity epidemic on type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Primary Care Diabetes, 16(6), 736–744. DOI: 10.1016/j.pcd.2022.09.006

- Jayedi, A., Soltani, S., Zeraat-talab Motagh, S., Emadi, A., Shahinfar, H., Moosavi, H., & Shab-Bidar, S. (2022). Anthropometric and adiposity indicators and risk of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ, 376, e067516. DOI: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067516